Chapter 6

From IQBAL

Chapter 6

THE SUPPORT OF MUSSOLINI TO INDIA

In spite of the fact that the preference of Fascism went to Tagore in the years 1925-1926 and to Gandhi in the Thirties, actually Mussolini was more favourable to Muslim Indians than to Hindu Indians, and this for many reasons: the Italian colonies were prevalently made up of Muslim subjects, commercial contacts had been established long ago with Mediterranean countries, the fairs of Bari (Fiera del Levante), Naples (Triennale d’Oltremare), and Tripoli (Fiera Campionaria), the fact that the Muslim Indians were stronger anti-British while the majority of their Hindu fellow-countrymen was in favour of a co-operation with Britain.

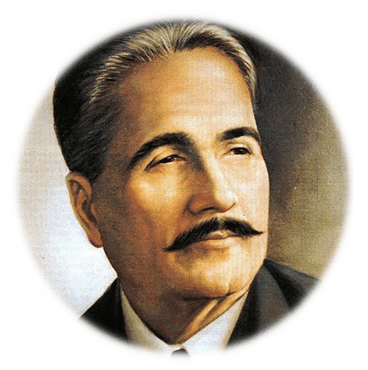

The most important Muslim representative in Italy was for more than twenty years Muhammad Iqbal Shedai. Born in a small village near Sialkot, in the province of Punjab, on 4th October 1888, Shedai studied at the Scotch Mission College (later renamed Murray College), the same of his famous fellow-citizen Allama Iqbal. Both of them were students of Maulvi Mir Hassan; though Allama was eleven years older than Shedai, they surely knew each other.1 In 1914 Shedai entered politics under the guidance of the brothers Muhammad ‘Ali and Shaukat ‘Ali,2 who were emergent personalities in the Muslim community: he joined the ‘Ali brothers’ organization Anjuman Khadami Ka‘ba, aimed to help pilgrims to Mecca. After teaching for a year at Hoti Mardan, Shedai was expelled from the North West Frontier Province because of his anti-British attitude. During the First World War he was interned by the British, as well as his protectors, the ‘Ali brothers, and released only in November 1918. In early 1920 a Hijrat Movement was started by Muhammad ‘Ali and ‘Abd ul-Majid Sindhi, who declared India as “dar ul-harb” [land of war] and exhorted Muslims to migrate to Afghanistan. Shedai reached Kabul where he was appointed by King Amanullah his Minister for Indina refugees. After working for the Afghan Department of Propaganda for two years he left for Moscow to study the Red Revolution; and from there he went to Ankara to discuss with Kamal Atatürk the problem of the Indian muslims in the Indian Army whom the Turks considered as responsible for their defeat in Iraq, Palestine, Lebanon and Syria during the First World War. In 1923 Shedai was sent to Italy with the task from the Hindustan Ghadar Party3 of starting contacts with the Fascist Government. In Rome he could contact some prominent people who introduced him into the world of governmental affairs, namely Carlo Arturo Enderle4 of Muslim origin, a neurologist, who was the adviser of the Opera Nazionale Balilla and an informer of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs; and the oriental scholars Ettore Rossi5 and Virginia Vacca6 of the University of Rome. In Milan he met in 1925 Luigi Lanfranconi,7 a member of the Parliament and president of the National Institute for Economic and Commercial Development, who was interested in India’s economy. In June 1926 an Indian delegation was in Milan to explore such possibilities to the extent of establishing an Italo-Indian bank: among the delegates there was Jawaharlal Nehru. Shedai was present and introduced Nehru to the fascist leaders according to a report8 written by Enderle for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In the same month Shedai met Mussolini’s brother, Arnaldo, at the premises of the newspaper “Il Popolo d’Italia”, and Piero Parini, a member of the editorial staff. Besides he met captain Giovanni Tavazzani, a member of the Military Information Service (SIM). However, Shedai’s contacts did not bring him much and at the end of 1926 the Ghadar Party decided to transfer him to Marseille to make propaganda among Indian sailors. Two years after he moved to Paris: there he married a French lady. At the outbreak of the Second World War, on plea of the British Government, Shedai was expelled from France because he was considered an Italian informer. His wife Bilquis got divorce and decided to live in London along with her daughter Shirin. From Paris he went to Switzerland staying in Lausanne; he was in friendly terms with the Italian Consul in Geneva, Renato Bova Scoppa, who had a high opinion of him and asked the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to help him to organize a reliable service of information. Unfortunately his activity against England was detected by the Swiss police and in October 1940 he was expelled from the territory of the Confederation: the logical choice for Shedai was to return to Italy. He reached Rome on 20th November and was asked to work under the orders of Renato Prunas, in charge of the department Transoceanic Affairs, and his substitute Rodolfo Alessandrini. However, he had always remained into contact with Italy through the Italian diplomats in Paris: he also attended the Congress of the Asiatic Students in Rome in 1933. From a note of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the Italian Ambassador in Paris on 11th December 1933 we learn he had an Italian passport issued by the Consulate General in Paris under the name of Mohammed El Hindi, Somali citizen: “The known El Hindi offered to co-operate to the meting of the oriental students which will take place in Rome on 21st instant under the auspices of the Institute for the East in agreement with this Ministry. Since we consider his co-operation useful, we are informing Your Excellency and the Consul General; however, it is advisable that the Italian authorities do not appear to be into contacts with El Hindi”. He had also offered his service in Ethiopia; in early 1935 he had advised that the conquest of Abyssinia would create a great enmity between Italy and Great Britain, which would eventually, in the long run, take to a war. The English considered that area their own zone of influence and did not allow any interference to their maritime routes. Hence Shedai advised to start a propaganda activity soon, before it was too late; but his offer was not accepted as the Italians did not want to be at daggers drawn with England in a period of impending war in Africa. Shedai, who was a patriot, thought that a war in Ethiopia would involve in the long run the British, who would thus be compelled to shift a large part of their Indian troops to Africa, leaving India defenceless and open to an internal revolt. And when war broke out, his Ghadar Party printed and distributed in India thousands of leaflets inviting the Indian troops to refuse to leave their country and to declare they were ready only to fight for the defence of their motherland. After the conquest of Ethiopia, Shedai again informed the Italian authorities that Britain had not accepted the Italian conquest and would, sooner or later, take her revenge:

According to the all the important men we have approached, in agreement with our personal opinion, England has received from the Italian occupation of Ethiopia such a serious loss of prestige as to shake the foundations of her Empire: it is a matter of life and death for the British Empire to regain her prestige in the world and all our information are confirming that, in order to punish Italy and to teach the world a lesson, England is making the biggest military effort as ever in history.9

Hence the Italian colonial empire was to be organized like the British India, completely self-sufficient and not depending economically and militarily on Italy. For this reason he suggested for Italy a period of ten-year peace so that she could be prepared to face a future war; actually this was also Mussolini’s idea. In fact, when on 1st September 1939 Hitler caused a war, Mussolini tried to postpone Italy’s entrance into the conflict by declaring the non-belligerency. Eventually, after the speed of the German victories, he made the mistake of entering the war, unprepared, on 10th June 1940: he had thought the war would be a matter of a few months, since he had excluded the entry of the USA, and that was the end of all. Ethiopia was not yet ready both from the economic and military points of view, the English fleet was able to cut the communications between Italy and the colonies of Libya and Ethiopia, and control the Mediterranean (Gibraltar, Malta, Cyprus, Egypt) and the Arabian Sea (Aden, Somaliland, South Africa, India). More or less, in the same period, in order to make propaganda among the Muslim Indians who were in favour of Abyssinia, the Italian consulates of Bombay and Calcutta tried to counterbalance the British propaganda by supporting those Muslims who looked at Italy with great expectations. The Italian consul in Bombay succeeded in obtaining in 1936 some funds from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to finance a bilingual English and Urdu newspaper “The Glance”, published by a young historian, Muhammad ‘Ali Salman, a great admirer of Mussolini and his policy. Another weekly newspaper in Hindi, “Lockandi Morcha”, addressed to the Hindus, was started in Bombay in July 1939: its editor, Damley, published Mussolini’s The Doctrine of Fascism, and some articles by Virginio Gayda. With the break of the war the Italian consulates were closed and this kind of propaganda was stopped. In Italy, in the years before the Second World War, Subhas Chandra Bose10 was considered the alternative to Gandhi’s non-violent movement. Bose, who at the age of 21 was a follower of Gandhi, soon became a strong supporter of a militant nationalism and of an immediate agitation against the British in India. In his inaugural speech as mayor of Calcutta, on 24th September 1930, first expressed his support for a fusion of socialism and fascism:

I would say we have here in this policy and program a synthesis of what modern Europe calls Socialism and Fascism. We have here the justice, the equality, the love, which is the basis of Socialism, and combined with that we have the efficiency and the discipline of Fascism as it stands in Europe today.11

His entente cordiale with the Indian Congress lasted until 1931: in December 1927 he became president of the Congress and in 1930 mayor of Calcutta. After being jailed by the British, in 1932 he was granted release subjected to his leaving the country; he chose Austria for his exile. From Vienna, where in 1933 he had written his book India’s Struggle for Independence, he started his contacts with Mussolini and prominent Italian people such as Gentile and Tucci. In December 1933 he attended in Rome the meeting of the students from Asia: on 28th December he was received by Achille Starace,12 who had been favourably impressed by his admiration of fascism and by his young spirit and creative enthusiasm.13 Actually Bose saw fascism a useful means of transforming the Indian sleepy society into a vibrant one; while Gandhi tried to compromise with the British, Bose, who held up an alternative vision, wanted immediate action against them. In the first months of 1934 Bose was received twice by Mussolini: on 6th January and on 28th April. Unfortunately there are no records of these two meetings. The only source is a letter from Bose to Mussolini on 29th November same year, when he was compelled to go back to India because of a serious illness of his father. In the letter Bose expressed his gratefulness to Mussolini for his support of the political problems of India:

Duce! Owing to the sudden illness of my father who is in a precarious condition, I have to fly back home at once. At the moment, I am passing through Roma on my way to India. I very much regret that owing to my sudden and unavoidable departure, I could not once more have the honour of calling on Your Excellency. I only hope that I shall be able to come back to Europe once again in order to finish my half-done task. I shall never forget the kindness I have received at Your Excellency’s hands – nor shall I ever forget the sympathy Your Excellency has shown for my unfortunate country. I carry home with me feelings of profound gratitude towards Your Excellency. I am sure Your Excellency will never forget that India expects much help and guidance from Your Excellency. It may be that Your Excellency is destined to play an important part in the liberation of my unfortunate country, as Your Excellency had already done in the case of Italy.14

However, it seems that, except from a verbal support, Mussolini had not until then committed himself. He was still hoping to come to terms with Britain and tried to avoid any open misunderstanding as possible: for example, on the occasion of Bose meeting Starace, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs disposed that press news were to be released after the official visit of the British Foreign Secretary, Sir John Simon, at the end of December 1933. Actually, every time Bose was received officially, the British ambassador in Rome, Eric Drummond, sent a note of protest against the audiences granted to a persona non grata. Two months after, Bose was again in Europe: on 25th January 1935 he was received by Mussolini to whom he explained his programme of founding an international league with the purpose of a close co-operation between the nationalistic parties and the oppressed peoples in order to start, at the right time, a simultaneous revolutionary movement.15 As for Bose, he exerted his influence in India in order to change the anti-fascist attitude of the newspaper “Forward” of Calcutta and tried in many ways to minimize the negative attitude of the Indian press on the occasion of the Italian conquest of Ethiopia. In a letter to Bose, the editor of the “Forward”: “I fully appreciate your attitude towards the Abyssinian question and I hope you have noticed a change in Forward articles on the subject”. In April Bose paid a visit to Romain Rolland, who was very impressed by him. Bose explained him why Gandhi’s non-violence was at a dead-point: in spite of Gandhi’s popularity among the masses, the population was not stimulated to action because of Gandhi’s policy of compromising. From Rolland’s diary it appears that Bose was convinced that India could get her independence only through violence and terrorist methods, or only if England was occupied in a not-to-far European conflict.16 After the Abyssinian war, Bose who had been labelled as a “pro-soviet subversive” became more important in the eyes of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who took the initiative and arranged a meeting with Mussolini for 27th March 1936. Of course the meeting had been prepared in advance; under the date of 15th February there exist a note by the Ministry about it:

We think it useful and opportune to contact Bose, before his leaving for India, by sending him to Paris one of our men and by inviting him to come to Italy. Before phoning him, we would like to know whether Your Excellency likes to meet him.

In December 1937, during a staying in Europe, Bose was elected president of the Indian Congress: on 20th January 1938 he was received by Ciano, who did not have a high opinion of the Indians. In his diary Ciano wrote: Bose, head of the Indian Congress, talked to me of the situation of his Party. So far the projects have been few. At the centre is Great Britain which has the full command. In the provinces some less important departments have been allocated to Indians. Great Britain has in small and big towns very good agents who oppress the population and find their support in the English troops. The program of his Party is: the independence of the Country. The means to reach it: obstructionism and passive resistance. No armed struggle. They ask us only two things: to continue to keep Great Britain worried about our intentions and to inform them regularly about the political situation in general; all this, so that they can better guide themselves. In my turn I suggested Bose to divert his sympathy to Italy and Japan, the two countries who have damaged the British more deeply. He told me he will try, but it is difficult because the Indian people are dominated by their sentiments, and today they are more favourable to China, just as in the past they were in favour of Ethiopia. In my opinion and on the basis of my short visits to India, I think the Indians are flabby people and un- reactive, who will never attain independence unless other forces bring about the collapse of Great Britain. And perhaps, even in that occasion, India will be submitted by a new master.17 At the beginning of 1939 Bose was re-appointed president of the Congress, in spite of Gandhi’s and Nehru’s opposition. Bose’s propaganda campaign in favour of totalitarian regimes in Europe was condemned by a large part of the Indian Congress. Nehru, whom the Fascists had vainly tried to have at their side, wrote:

He [Bose] did not approve of any step being taken by the Congress which was anti-Japanese or anti-German or anti-Italian. And yet such was the feeling in the Congress and the country that he did not oppose [any] manifestations of Congress sympathy with China and the victims of fascist and nazi aggression. We passed many resolutions and organized many demonstrations of which he did not approve during the period of his president-ship, but he submitted to them without protest because he realized the strength of feeling behind them. There was a big difference in outlook between him and others in the Congress Executive, both in regard to foreign and internal matters, and this led to a break early in 1939.18

We have said that Nehru was one the goals of fascism: he was considered an intelligent and shrewd politician and one of the most probable successors to the Mahatma, as later on it turned to be. Nehru too had been intrigued by Mussolini’s personality, but however he did not fall into the trap due to some circumstances. The occasion was in March 1936; actually a meeting had been scheduled for 1st March, but Nehru’s wife died the day before, on 28th February in Switzerland; the visit was then postponed to 7th March, but this too was cancelled because of Nehru’s bad health, or perhaps because of a diplomatic illness as it is guessed from Nehru’s memoirs:

During our stay at Montreux I had a visit from the Italian Consul at Lausanne, who came over especially to convey to me Signor Mussolini’s deep sympathy at my loss. I was a little surprised for I had not met Signor Mussolini or had any other contacts with him. I asked the Consul to convey my gratitude to him. Some weeks earlier a friend in Rome had written to me to say that Signor Mussolini would like to meet me. There was no question of my going to Rome then and I said so. Later, when I was thinking of returning to India by air, that message was repeated and there was a touch of eagerness and insistence about it. I wanted to avoid this interview and yet I had no desire to be discourteous. Normally I might have got over my distaste for meeting him, for I was curious also to know what kind of man the “Duce” was. But the Abyssinian campaign was being carried on then and my meeting him would inevitably lead to all manner of inferences, and was bound to be used for fascist propaganda. No denial from me would go far. I knew of several recent instances when Indian students and others visiting Italy had been utilized, against their wishes and sometimes even without their knowledge, for fascist propaganda. And then there had been the bogus interview with Mr. Gandhi which the “Giornale d’Italia” had published in 1931.19

In spite of this attitude, Shedai considered Nehru a probable sympathizer of fascism: this idea was based on the fact of Gandhi’s and Nehru’s attitudes towards Britain. According to Shedai Gandhi was more favourable to British proposals, while Nehru was more pragmatic in his attitude and did not like the Mahatma’s conciliatory tendency. Though Shedai’s analysis was correct, Gandhi and Nehru agreed fully on the main problems: their differences were only formal due to their different personalities. In fact, when Gandhi retired temporarily from politics in 1935-36, he handed the direction of the National Congress over to Nehru. Nehru was adamant in his policy, both internal and international. When the Second World War was approaching, the Congress was compelled to pay attention to foreign developments. Nehru’s main fear was for Hitler’s aggressive attitudes; he considered Mussolini a man who “did not then appear as a major threat to world-peace”. He expressed his view in his Discovery of India, written later on, in the Ahmadnagar Fort Prison Camp from 9th August 1942 to 28th March 1945:

It is surprising how internationally minded we grew in spite of our intense nationalism. No other nationalist movement of a subject country came anywhere near this, and the general tendency in such countries was to keep clear of international commitments. In India also there were those who objected to our lining up with republican Spain and China, Abyssinia and Czechoslovakia. Why antagonize powerful nations like Italy, Germany and Japan, they said; every enemy of Britain should be treated as a friend; idealism has no place in politics, which concerns itself with power and the opportune use of it. But these objectors were overwhelmed by the mass sentiment the Congress had created and hardly ever gave public expression to their views.20 NOTES AND REFERENCES