Chapter 4

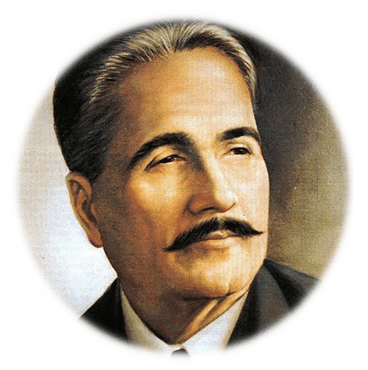

From IQBAL

Chapter 4

GANDHI’S VISIT TO ITALY

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the Mahatma, came to Italy a few days after Iqbal. Released from jail on 25th January 1931, the Mahatma left Bombay on next 29th August bound to London where he arrived on 12th September. He had gone to England, like Iqbal, to attend the Second Round Table Conference; he was accompanied by his son Devadas, his two secretaries Mahadev Desai and Nayar Pyarelal, and his faithful follower Mirabehn, actually Miss Madeleine Slade, an English woman who had been living for years in India. The Conference, which ended on the first days of December, was a failure. On his way back to India on 5th December, the Mahatma stopped at Paris, and on 6th morning he proceeded for Switzerland to meet Romain Rolland at Villeneuve; his staying there from 6th to 10th was very fruitful, as we can see later on. On 11th December he left for Rome via Milan, and on 14th morning he boarded a ship at Brindisi, bound to Bombay where he arrived on 28th December. The first idea of inviting Gandhi to visit Italy is ascribed to the Italian Consul General in Calcutta, Gino Scarpa, a sort of longa manus of Mussolini in the Indian sub-continent. Scarpa, who had been a socialist in 1913, had entered the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce (later, National Economy) after the First World War: in 1923 (or 1924) he was sent to Bombay with commercial assignments. In 1928 he joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and was sent Consul to Colombo, Ceylon (present Sri Lanka) and from 1929 to 1932 to Calcutta as Consul General. Since his arrival to India he had created his own commercial and political network, being acquainted with many members of the Indian Congress, in particular with Gandhi’s secretary Mahadev Desai. Scarpa, who was greatly in favour of Gandhi’s nationalism, had sent in April 1930 a telegram to the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, underlying two facts: the favourable acceptance by the Indian press of a Vatican report concerning the role played by Gandhi and a press report by the Jesuits in India in favour of the nationalist movement. In the same period Gino Scarpa had published a book L’India dove va?, we have dealt with in our Introduction, in which he had expressed his own points of view on the matter, of course in agreement with the Government. As soon as the rumour of Gandhi’s visit to Europe was spread in June 1931, Scarpa started thinking of a visit of the Mahatma to Rome. However, he was aware of the difficulties since the Ministry, as with the case of Iqbal, was worried of the English reactions. Besides he knew that important Italian persons, such as the Minister of Foreign Affairs Dino Grandi and the philosopher of the regime Giovanni Gentile, were pro-British and did not intend to create misunderstandings with the English. Consul Scarpa went on with his project, probably through a friend of his, Ghanshyam Das Birla, who wrote to Gandhi about the invitation; the proof is a letter of the Mahatma to G. D. Birla, on 26th July, stating: Please thank the Italian Consul for the very kind offer made in connection with the probable visit by Malaviyaji1 and myself to Rome. Nothing is certain with reference to my visit to London and even f I succeed in going there I do not know that I shall be able to visit Italy on my return. On going to London there is no possibility of my visiting Rome. I believe the same thing applies to Malaviyaji.2 Actually the Mahatma had excluded any visits to Italy: also his attending the Round Table Conference was uncertain due to the unfavourable relations between the Indian National Congress and the British authorities in India in that period. Only at the end of August did Gandhi decide to attend the London Conference after a meeting with the Viceroy in Simla; on 26th August a press release announced it:

Mr. Gandhi had three hours’ satisfactory talk with the Viceroy at the end of which he informed the Associated Press that he would be sailing from Bombay on 29th instant.3

The Mahatma must have taken a decision when in London. In autumn 1931 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs wrote to Gentile that “Gandhi’s position in the eyes of the English government does not allow us to receive him officially, though he might be invited by a cultural institution”.4 To prepare a favourable ground for the visit, it was thought of an escamotage: Gandhi would be invited by the “Accademia d’Italia” and not by the Ministry. In this way no objection would be raised; the Italian ambassador to London, agreed upon it, writing on 12th October 1931 to the Ministry: There is no objection to the invitation of Gandhi and other Indian personalities by the “Accademia d’Italia” or similar institutions.5 No meeting between Gandhi and Mussolini was talked of. Nothing was said in a letter to Gino Scarpa from the Mahatma’s secretary Mahadev Desai: He [Gandhi] would be quite agreeable to address the students under the auspices of the Milan and the Rome universities on the spiritual message of non violence or some such thing. But here too he would be agreeable to whatever you may desire. But you please avoid more than one lecture, for he is exhausted and weak. You can get him to meet as many public-men as you like of course.6 Actually it was followed the same procedure used for Iqbal. A month before Gandhi’s arrival to Italy, the Ministry was still of the idea of “an invitation by the Institute for Fascist Culture or by the University of Rome”; as a matter of fact, a sympathetic attitude to Gandhi at official level cannot be denied. Gentile himself, who had written a preface to the Italian edition of Gandhi’s biography which appeared at the end of 1931,7 was very cautious and had sent Gandhi a diplomatic telegram saying he was sorry that during his scheduled staying in Roma he could not meet him as he was out of town. Actually Gentile had invited Gandhi to speak in Rome at the Istituto Nazionale di Cultura Fascista; the telegram, dated 4th December 1931, addressed to Desai read:

Please ask Mahatma whether passing through Rome would like accept invitation Istituto Nazionale Fascista Cultura addresses through me to call at Istituto and speak select audience stop. Please moreover advise date arrival stop. Best regards. President Senator Gentile.8

The answer was astonishing:

Thanks. Gandhiji will gladly address if you have no objection is freely criticism Fascism stop. If agreeable we can reach Rome Saturday morning eight thirty wire Mahadev Desai.9

Hence the diplomatic telegram from Gentile’s office, saying that the Senator was out of Rome until next Monday. However, the Consul General Gino Scarpa went on with his underground work in order to arrange for Gandhi’s visit and for his meeting Mussolini. Gandhi’s visit to Roma was at last scheduled for 12-13th December 1931. Before reaching Rome, the Mahatma had been a guest of Romain Rolland, who wrote a long report in his Inde. Journal (1915-1943). Rolland10 informed Gandhi of the moral and social situation in Europe after the First World War and of the danger of an impending, more devastating war. Then he discussed of the methods to prevent it: violence or non-violence? Finally he prospected to Gandhi the dangers of his visit to Italy and reminded him of the consequences of Tagore’s visit. In Italy he would be in the hands of the Fascists and would be surrounded by journalists, high officials and government spies, all of them interested in exploiting him: whatever he would do or say would be reported in a distorted way. On Tuesday 8th December Rolland and Gandhi discussed the problem of Italy. Gandhi told him he had been invited through the good offices of consul Scarpa and would be interested in meeting Mussolini: I wish to go and to meet Mussolini. I wish to meet people, to bring them my mission of peace [...] I wish to meet the Pope who sent me a good message [...] Scarpa [...] assured me that my visit is private, non-official, arranged by himself [...] About Mussolini, I do not think he wants to see me, but if he wants, I will do without any hesitation.11 Rolland asked Gandhi to re-consider his purpose: any meeting with official representatives would appear as a support of the regime. He suggested to meet only the Pope and to speak only at the presence of foreign journalists and his own faithful people, such as Desai and Mirabehn. When Rolland realized that Gandhi intended to visit Italy, he asked him not to accept the invitation of Countess Carnevale,12 a pro-regime lady, but to stay at the Rome residence of general Moris13 whom he considered a trusty-worth gentleman. The Mahatma reached Rome on 12th December early morning. The first surprise came from the Vatican: the Pope regretted he could not meet Gandhi because time was short. However, Gandhi visited some halls of the Museum and the Sistina Chapel. At 6 p.m. he was received by Mussolini at Palazzo Venezia, along with Desai, Mirabehn and Moris; no official reports were issued of the twenty-minute meeting except what published in newspapers, i. e. two lines saying: “The Head of the Government has received at Palazzo Venezia the ‘Mahatma’ Gandhi who had expressed the wish to meet him on the occasion of his voyage to Rome. The visit lasted about twenty minutes”.14 Why this change of attitude? It was said that the visit to Mussolini was a private one: what difference was there between a private visit and an official visit? The fact is only one: Gandhi met Mussolini. Did have any meaning the fact that Gandhi had not been received by the Minister of Foreign Affairs Dino Grandi? Was it possible that a fascist diplomat such as Scarpa could organize the meeting without the support of his Ministry? Or probably Mussolini had changed his mind at the last moment. Many years after, in 1959, Scarpa wrote that on the day of Gandhi’s arrival he was told not to go to the station and not to contact Gandhi in any case; but a few hours after, the Ministry changed mind and ordered him to accompany the Mahatma.15 Of course there are no reports of the meeting; only some passing words. For example Rolland reported something Gandhi wrote him in a letter:

On the whole he does not look a very understanding person, but he has been charming with me; and when I told him that the Pope could not receive me, his eyes flashed with mischievous satisfaction.16

More extensive and informative was Gandhi’s thought about Mussolini and Fascism in a letter written to Rolland on 20th December from aboard the ship in his voyage back to India:

Mussolini is a riddle to me. Many of his reforms attract me. He seems to have done much for the peasant class. I admit an iron hand is there. But as violence is the basis of Western society, Mussolini’s reforms deserve an impartial study. His care of the poor, his opposition to super-urbanization, his efforts to bring about co-ordination between capital and labour, seem to me to demand special attention [...] My own fundamental objection is that these reforms are compulsory. But it is the same in all democratic institutions. What strikes me is that behind Mussolini’s implacability is a desire to serve his people. Even behind his emphatic speeches there is a nucleus of sincerity and of passionate love for his people. It also seems to me that the majority of Italian people love the iron government of Mussolini.17

It was a very clear and lucid examination of the situation: the Mahatma had caught the real situation of Italy and the contradictions of a dictatorial regime with its advantages and disadvantages. However what Mussolini and Gandhi may have said in their short meeting was unimportant; from the various known sources, mostly oral, the talk seemed not to have had any political relevance.18 The only interesting report was written by Mahadev Desai, under the form of personal notes in Gujarati,19 which were never disclosed. From it we know that Mussolini’s main questions concerned: the Round Table Conference, the economical situation in India, Gandhi’s program, the Hindu-Muslim problem, the independence of India and the form of government, the situation in Europe. Gandhi’s answers were short and uncompromising; neither Mussolini nor Gandhi spoke about the Italian political situation. Of some relevance would have probably been the letter Gandhi wrote to Mussolini from aboard the ship on 21st December, if this letter could had been traced.20 The importance was only the fact of their meeting: for Mussolini it was the affirmation of his personal policy and a sort of warning to Britain, for Gandhi it was a sort of personal satisfaction and maybe an innocent demonstration of his leadership, a kind of message to the Indian nationalists then divided between the use of violent or non-violent means of struggle. More relevant and provoking was the so-called interview, which was published in the Rome newspaper “Giornale d’Italia” on 15th December. Most probably it was a bogus. Virginio Gayda, the director of the newspaper, a man close to the government, in particular to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said that the interview was granted to him by the Mahatma. Gandhi and his people denied it. Gayda, whose fluency in English is not known, must have picked up pieces of conversations at a gathering at Countess Carnevale’s house in Rome and must have joined them, adding his own opinions and making up an interview. Probably there was also some connivance by government quarters in order to create embarrassment in the Italian relations with Britain. In fact this so-called interview was re-published by other Italian newspapers with great propaganda; we must not forget that the press was government-controlled and some orders from above must have been given to publicize this so-called interview. In the article it was said that Gandhi considered the Round Table Conference in London a failure and that he intended to increase his fight against the British Government and to boycott English goods. These words, reprinted in “The Times”, caused a great stir in England, and Samuel Hoare,21 Secretary of State for India, asked Gandhi for an explanation. According to “The Times” report, the cable sent to Gandhi was as follows: Press reports state, on embarkation, you issued to “Giornale d’Italia” a statement which contains expressions such as following:

(1) Round Table Conference marked definite rupture of relations between India nation and British Government. (2) You are returning to India in order to restart at once struggle against England. (3) Boycott would now prove powerful means of rendering more acute British crisis. (4) We will not pay taxes, we will not work for England in any way, we will completely isolate British authorities, their politics and their institutions, and we will totally boycott all British goods.

Some of your friends here think you must have been misreported and, if so, denial desirable.22 Needless to say that Gandhi answered he had never given any interview while in Italy; from Port Said Gandhi answered on 17th December:

Giornale d’Italia” statement wholly false. Never gave any interview pressmen Rome. Last interview I gave was to Reuter Villeneuve where I asked people India not come hasty decision but await my statement.23

Notwithstanding Gandhi’s disclaimer, Virginio Gayda persisted in his claim that the interview was genuine. The result, however, was that back to India, Gandhi was arrested. The cause was not surely the interview; anyhow it contributed to his arrest and jail.24 To make things worse was also his speech at the Welfare of India League, at Bombay, on his arrival. To the question: “If you were in power, would you allow another organization to run a parallel Government and usurp your place?”, Gandhi answered:

When I said that I did not see any harm in organizations running parallel Governments, I did not mean usurpation. My friend has put a word into my mouth which I never used. If these organizations run a parallel Government for the good of the people, I would certainly give them all encouragement. See what Dictator Mussolini is doing in Italy. He never interferes with voluntary activities for the betterment of the country.25

The problem of the interview must have been important if Gandhi felt obliged to send to Samuel Hoare a new detailed report of the facts, three years after, on 6th March 1934.26 Gandhi started his letter by saying that “an English friend, Prof. Maclean of Wilson College, Bombay, had thought that, although the matter was stale, it was worthwhile my clearing up, as the denial by the Rome journalist had created a profound impression at the time of its publication and had probably precipitated the Viceregal action against me in 1932”. After summarizing the main points of the so-called interview, based on three cuttings from newspapers27 he had seen for the first time after being released from jail, Gandhi stated:

1. I never made any statement, much less a long one to Signor Gayda. 2. I was never invited to meet Signor Gayda at any place. But I was invited by an Italian friend [Consul Scarpa]28 to meet some Italian citizens at an informal drawing-room meeting at a private house [Countess Carnevale]. At this meeting I was introduced to several friends whose names I cannot now recall and could not have recalled even the day after the meeting. The introductions were merely formal. 3. At this meeting the conversation was general, and not addressed to any particular individual. Questions were put by several friends and there was a random conversation as at all drawing-room meetings. 4. It was therefore wrong for Signor Gayda or “The Times” correspondent to reproduce my remarks as if they were one connected statement to one particular person. 5. Signor Gayda never showed to me for verification anything he might have taken down. 6. The conversation, among other things, referred to the Round Table Conference, my impression of it and my possible further action [...]. 7. I never said that I was returning to India in order to restart the struggle against England [...].

Nehru himself mentioned this interview and its effects when he spoke of Mussolini’s invitation to him in 1936 and his denial to accept it:

[...] the Abyssinian campaign was being carried on then and my meeting him would inevitably lead to all manner of inferences, and was bound to be used for fascist propaganda. No denial from me would go far. I knew of several recent instances when Indian students and others visiting Italy had been utilized, against their wishes and sometimes even without their knowledge, for fascist propaganda. And then there had been the bogus interview with Mr. Gandhi which the “Giornale d’Italia” had published in 1931.29

To conclude this chapter of the visit, the position of Consul General Scarpa in the arrangement of Gandhi’s visit was emphasized by Gandhi himself in a letter to him from Bombay on 3rd January 1932:

Just a line, whilst I am yet free, to thank you for your kindness during my all too brief stay in beautiful and historic Rome. I wish I had two months instead of only two days. Please tell the [Lloyd] Triestino Agent with my thanks that the Commander and the officers of s.s. Pilsna made me and my party thoroughly comfortable.30

The problem of Mussolini was faced accidentally in May 1938 after the Abyssinian conquest. Gandhi, who was touring in the North-West Frontier Province, was asked to say his opinion from the non-violence point of view. The Mahatma gave an answer in conformity with his credo, but unconvincing on a practical level:

Non-violence is the activest [sic] force on earth, and it is my conviction that it never fails. But if the Abyssinians had adopted the attitude of non-violence of the strong, i. e. the non-violence which breaks to pieces but never bends, Mussolini would have had no interest in Abyssinia. Thus if they had simply said: ‘You are welcome to reduce us to dust or ashes but you will not find one Abyssinian ready to cooperate with you’, what would Mussolini have done? He did not want a desert. Mussolini wanted submission and not defiance, and if he had met with the quiet, dignified and non-violent defiance that I have described, he would certainly have been obliged to retire. Of course it is open to anyone to say that human nature has not been known to rise to such heights. But if we have made unexpected progress in physical sciences, why may we do less in the science of soul?31

For the sake of information, it is interesting to record two very little-known open letters written by Gandhi to Hitler and Mussolini during the war, which were suppressed by the British Government in India. They are typical of Gandhi’s personality, though he himself realized the usefulness of them. The two letters are dated 23rd July 1939 and 24th December 1940; they were both addressed to Hitler and dealt with the problem of the unjustness of any war. The fault of the war – thought Gandhi – was only of their leaders: “neither the Englishmen and Germans nor the Italians know what they are fighting for except that they trust their leaders and therefore follow them”. The second letter ends by saying:

I had intended to address a joint appeal to you and Signor Mussolini, whom I had the privilege of meeting when I was in Rome during my visit to England as a delegate to the Round Table Conference. I hope that he will take this as addressed to him also with the necessary changes.32

It is difficult to say whether the Mahatma hoped in a positive answer; was he so simple minded? Not at all; most probably his intention was to publicize in Europe the technique of non-violent resistance since he was aware that it was little understood in the West, especially in its positive and reconciling sense, and for that reason, apart from any other, his appeals had not met with any wide response.

NOTES AND REFERENCES