Chapter 1

From IQBAL

Chapter 1

INDIA IN THE FIRST HALF OF 20TH CENTURY

The Revolt of 1857-58 was for the British in India a signal that something had changed; though it was mainly feudal and limited to some parts of India, it had shaken the British administration from the bottom. After the assumption of the direct administration of India by the Crown something moved, though slowly, in the field of education: between 1857 and 1887 five universities were founded (Calcutta, Bombay, Madras, Lahore, and Allahabad). However a true silent revolution started when the English language and culture spread all over the Indian subcontinent: Indians, mainly Hindus, were thus able to look to English liberalism and institutions for inspiration. The few hundreds students, who could benefit of the English language as the medium in higher education in India before the Revolt, became many thousands by the end of 19th century. It was this system of education that became the vehicle of Western culture and brought about a real revolution in India. The new Western learning dispensed in the English high schools and colleges exerted a big influence, thus facilitating the Indian recovery; by it India shared in the rich legacy of science and rational thought that was the product of the 19th century. Even though the number of these Western-educated Indians has never been large, two and a half million in the 1920’s, the seed had been sown.1 The second step was the foundation of political parties. The first was the Indian National Congress which met in Bombay during the Christmas week of 1885. It was created by an English retired civil servant, Allan Octavian Hume, with the initial consent of the Governor-General who had thought of it as a place for discussions only: on the contrary, its objective was, indirectly, to be “the germ of a Native Parliament”, a sort of “constitutional channel for the discharge of the increasing ferment which had resulted from western ideas and education”.2 In the beginning the Congress was a body open to all and in five years the attendance of Muslims increased from 2 out of a total of 70 in 1885 to 156 out of a total of 702 in 1890. In 1905 the attendance of Muslim dropped to 17 out of a total of 756. It had happened that the Muslims had realized the Congress was going to transform the nationalist movement from a purely secular to a politico-religious one. Besides, in the background, the English were probably working in order to split the party to better control it. However, it is true that the Muslims were discriminated, but this was because they were far behind the Hindus in respect of Western learning. It was Syed Ahmad Khan, the leader of the Muslims, who found the remedy for the backward situation of his co-religionists; he promoted English education through a school which became, later on, known as the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College of ‘Aligarh. In the long run, this situation brought to the creation of a Muslim party, the Muslim League, which was founded at Dacca in 1906. In a few years the British became aware of the true soul of the Congress. Lord Curzon himself, an ardent student of Indian history, who at the beginning of his viceroyalty (1899-1904) was really interested in facing the country’s problems, went back on what he had thought of before when he realized of the growing national sentiment inside the Congress. The first demonstrations of this insurgent nationalism were the reforms of education which culminated with the Universities Act of 1904 and of administration in Bengal with the partition into two separate provinces in 1905. These two acts were partly responsible for the Congress uncompromising declaration regarding self-government [swaraj] in 1905 and for the creation of the Muslim League in 1906. Though the partition of Bengal was by itself a reasonable administrative act, it was wrong from the political point of view because it interfered with “the growth of a true national spirit transcending creed and community. The partition of Bengal, carried out despite the strongest opposition from Nationalists, whose leaders included both Hindus and Muslims, roused a fierce spirit of resistance among them, and gave a new turn to the political movement”.3 The situation worsened all over India, in particular in Bengal and in Punjab where popular unrest resulted in many extremist actions. The government resorted to repressive methods, but contemporarily tried to moderate the situation by granting the Morley-Minto Reforms of 1909, that is including an Indian member in the Governor-General’s Executive Council, and by modifying the partition of Bengal in 1911. Unfortunately the 1909 reforms contained a new element of dissension inside the Congress, by providing separate electorates for the Muslims: all the Hindus representatives in the Congress, Moderates and Radicals, considered it an act by the British to divide the Indian community. No need to say that the introduction of the separate electorates was deliberately carried on by the British Government to set the Muslim League against the Indian National Congress. At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 many politicians in Europe, particularly in Britain, thought this would be the occasion for Indian Nationalists to stab the English in the back and to throw off the yoke of the British raj. On the contrary, India as a whole supported Britain in her war against the central Empires: British India and the Native States of India, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs declared in favour of the Allied cause. The contribution of men, arms and money was enormous: more than 26,000 Indian soldiers were killed and 70,000 were wounded. In December 1916, for the first and only time, the Congress and the League made an agreement, the “Lucknow pact”, in force of which the Congress accepted the project of separate electorates, and the two organizations started working jointly for a constitutional scheme on the basis of Dominion status. In the period 1915-16 the new generation of nationalists insisted for self-government: the younger intellectuals, both Hindus and Muslims, were becoming more nationalistic than their old leaders. Their hopes increased when Edwin Montague became State Secretary for India: on 20th August 1917, in the House of the Commons, he announced that “the policy of His Majesty’s Government, with which the Government of India are in complete accord, is that of the increasing association of Indians in every branch of the administration and the gradual development of self-governing institutions with a view to the progressive realisation of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British Empire”. At the end of the year, on 10th November, Montague arrived in India for a long tour until 23rd April 1918: on 26th November he met at Delhi the delegations representing the Congress and the Muslim League, among them old Surendranath Banerji, ‘Ali Jinnah, Gandhi, and Tilak who “came with [his] Home Rule League”.4 The result was the Montague-Chelmsford Report which was published on 8th July 1918. Though this report constituted an improvement of the Morley-Minto scheme of government, it was considered unsatisfactory after India’s tremendous support to Britain during the war. The left wing of the Congress, guided by B. G. Tilak,5 opposed it as inadequate, disappointing and unsatisfactory. Again the Congress split into two sections: the moderates and the radicals; however, pending the war, the Congress continued in its co-operation with Britain. 1919 was the key year. In January the US President, Woodrow Wilson, enunciated the Fourteen Points which spoke of self-determination of nations: India started hoping in a self-government of her own. At the same time two events created new embitterment in the country: the coercive measures of the “Rowlatt Act” which authorised imprisonment without trial and the massacre by the British army at Amritsar during a peaceful meeting of protest. Besides, the Muslim community was offended by the dismemberment of the Turkish empire and by the end of the Caliphate.

And then Gandhi came – as Jawaharlal Nehru wrote in his Discovery of India - political freedom acquired a new content. [...] A new technique of action was evolved which, though perfectly peaceful yet involved non-submission to what was considered wrong and, as a consequence, a willing acceptance of the pain and suffering involved in this. Gandhi was an odd kind of pacifist for he was an activist full of dynamic energy. There was no submission in him to fate or anything that he considered evil; he was full of resistance though this was peaceful and courteous.6

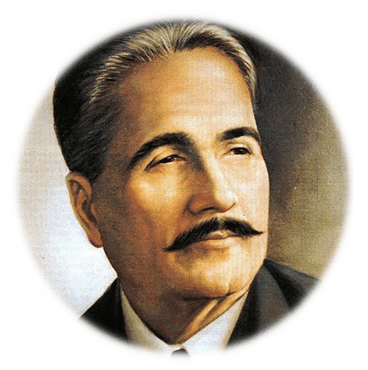

From now on the political scene of India will be dominated by the powerful personality of Gandhi: loved by his people, criticized or hated by many others, he was respected by all, the British included. Non-violence [ahimsa] and truth-force [satyagraha] were the pillars of his belief; after experimenting them in South Africa, the Mahatma returned to India in 1914 and in May 1915 established an ashram at Ahmedabad with a bunch of disciples who had the task of teaching his ideas to the Indian masses. The first practical enforcement of his credo was the hartal Gandhi called against the “Rowlatt Act” for 30th March 1919, postponed to 6th April. Unfortunately the new date was not known in Delhi and the hartal took place there on 30th March: some shop-keepers at the railway station did not observe it, there were riots, police intervened and some people were killed during the disorder. Gandhi had decided to visit Delhi and Amritsar in the Punjab: for fear of disturbances it was forbidden to Gandhi to go to the Punjab: he was arrested and sent back to Bombay. The news of Gandhi’s arrest created problems in the area, but the biggest incident took place at Amritsar in early April; after days of rioting, on 13th April a big crowd collected at Jalyanwala Bagh for a peaceful protest, unaware or ignorant of a military order which forbade any meeting. General Dyer arrived at the garden with his Gurkha troops and, without any warning, ordered to fire. It was a massacre which embittered for years the Anglo-Indian relations: Gandhi was shocked and suspended passive resistance. He resumed it a year after on the occasion of the Caliphate movement to support the Muslims: the National Congress met at Calcutta in September 1920 and passed Gandhi’s proposal of “progressive non-violent non-cooperation”, which meant an almost complete stop to the main activities all over the country. This was a shrewd device to unite the two major communities in India: the climax was the burning of foreign cloth in 1921, which unfortunately produced the violent rebellion of the Muslim Moplahs in the province of Madras. Incidentally, as already mentioned in the Introduction, this was the subject of Mussolini’s first article dealing with the Indian problems: for the future Duce the independence of India was prophetically “not a matter of possibility, but a problem of time”.7 Another violent incident took place in February 1922: a mob set fire to a police station at Chauri Chaura, in the United Provinces, burning to death twenty-two policemen. Again Gandhi suspended the civil disobedience: many members of the Congress, included Jawaharlal Nehru, did not agree. Could an isolated episode influence a national struggle and frustrate the efforts of hundred thousands patriots? However, Gandhi’s personality prevailed and the Congress accepted his decision. Gandhi was put to trial by the Government and sentenced to six years in jail: the trial seemed to have come out of Socrates’ pages of Apology where the judge is sorry to inflict a penalty and the defendant is asking for the maximum of penalty. The Mahatma retired from politics and the direction of the Congress passed into the hands of C. R. Das and Motilal Nehru. Though Gandhi was released in February 1924, earlier than foreseen, he decided stay away from the activity of the Congress and to concentrate on the problem of removing untouchability. In this period there emerged in the Congress a younger generation of politicians, more radical: the prominent among them were Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, whose goal was a complete national independence. On the contrary, the Government was now ready to grant India the status of Dominion: “[...] it is implicit in the declaration of 1917 that the natural issue of India’s constitutional progress [...] is the attainment of Dominion status”. There was now a wide gap between the two positions, and the government offered to hold in London a Round Table Conference. In the meantime, new facts had altered the whole scene. The Indian National Congress and the Muslim League separated definitely: Gandhi returned to active political life in order to compose the gap between moderates and extremists inside the Congress; ‘Ali Jinnah left the Congress and later on left India for London where he worked as a lawyer, in a sort of voluntary exile until 1936. To support the 1929 Congress’ request for complete independence, Gandhi resumed the weapon of civil disobedience. On 12th March 1930 he defied the Government on the salt tax by starting a long march from Ahmedabad to the sea: on 6th April he violated the law by extracting symbolically some grams of salt from sea-water. This event marked the beginning of a new civil disobedience: great emphasis was given to it in the newspapers all over the world. The Mahatma was arrested on 5th May; along with him 60,000 satyagrahi, as his followers were called, were jailed. As already announced, the First Round Table Conference took place in London from 12th November 1930 to 19th January 1931: it was attended by some ten princes and by Muslim delegates, among whom the Agha Khan8 and ‘Ali Jinnah,9 the Congress was absent. In spite of the heavy agenda and the bulky work, the proceedings of which filled eight volumes, the results were almost nil except the official approval of the obsolete principle of a federal government for India. A second Round Table Conference was scheduled from 7th September to 1st December 1931: Gandhi was released in Spring 1931 and the Congress approved to be represented solely by him at the Conference. At the second Conference, besides M.A. Jinnah, there was the revered Muslim poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal10 who had a great influence on Jinnah, though, at the time, their opinions diverged: in 1930 Jinnah still believed in the unity of Muslims and Hindus, while Iqbal, at the Muslim League session in Allahabad, had said that “to base a constitution on the conception of a homogeneous India, or to apply to India the principles dictated by British democratic sentiments, is unwittingly to prepare her for a civil war”. Scarce was the result of this second Conference because of the disagreement between Gandhi and the Muslim delegation. It was this the period in which the fascist government in Italy tried to take advantage, from a propagandistic point of view, of the fact that many Indian delegates to the Second Round Table Conference were passing through Rome in order to board a ship at Brindisi or at Venice on their way back to India. A confidential report, most probably written by the Italian Consul General in Calcutta, who was in those days in Rome, dated 8th October 1931 said:

It would be convenient to inquire whether the delegates intend to remain in Europe waiting for the re-convocation or to go back to India. In both cases, particularly in the first case, there are possibilities of some of them coming to Italy.

1-The “Accademia d’Italia” has already invited Dr. Sir M. Iqbal: on the occasion, other Muslim leaders are surely coming. 2- The two representatives of the Federation of the Indian Chambers of Commerce expressed to me, while in India, their wish to visit Italy and to meet important persons of our economical world. One of these is Mr. Dirla, who controls the jute market in Calcutta (Two years ago he gave a tea-party in honour of the Duce’s daughter, which was attended by 300 people). Concerning these delegates, for whom I think there are no objections, it is necessary to know the form of assistance to be given and to see whether a particular invitation is to be sent (Fascist Federation for Industry, University “Bocconi”,11 or similar). 3- There is also a possible visit of the two hindu leaders Gandhi and Malaviya (the chancellor of Benares University where a lecture on “Fascism and the Duce” was held two years ago at the presence of two hundred professors and all the students). It is also possible they intend to pay a visit to the Pope. In April 1930 the Press Agency of the Holy See, at the beginning of Gandhi’s campaign published a note declaring that the Vatican did not have any objection to a possible autonomy of India and to Gandhi’s ideas, asking only for an assurance about the situation of Catholics in India. This visit is meant to give such assurance and to get at the same time the sympathies of the Vatican. I would like to have instructions in case of the visit of these two leaders. Since a Muslim leader [Iqbal] has been invited, it might be convenient, under certain aspects, to invite the Hindu leader [Gandhi] in order not to hurt the feelings of his community of two hundred and eighty million people.12 The Hindus and the nationalists in particular do not support the recent campaign of lies and boycotting against Italy and the Duce, for whom they show their sympathy. For my knowledge of Gandhi I can say he is much different from Tagore; he has always refused to express judgements on people and forms of government in other Countries – and I do not think he will behave differently. If his visit is considered useful, I think we must approach him and explain him that there would not be any advantage for the interests of our two Countries for him to express any judgements on the regime. In case he agrees, we can rely on his complete discretion.13 Back to India, Gandhi revived civil disobedience and was sent again to jail. The situation for the British in India had come to a head: besides, in the North-West Frontier Province, an important but difficult area to rule, a party had been formed in 1930 by ‘Abd al Ghaffar Khan, a Muslim who, like Gandhi, preached nationalism in a non-violent way: the party of the “Servants of Allah” [Khuda-i Khidmatgar], called “Red Shirts” [Surkh Posh] because of their garments, was affiliated to the Congress. It was unusual to see Pathans, known for their martial attitudes, preaching non-cooperation among the peasants and inviting them not to pay taxes; and more unusual was that a province with ninety per cent Muslims was a Congress stronghold. The third and last Round Table Conference took place from 17th November to 24th December 1932. The Congress was not represented, Jinnah did not attend it because he had not been included in the delegation on the ground that “he was not thought to represent any considerable school of opinion in India”.1414 Disillusioned with politics, Jinnah settled in London looking after his legal profession; years later, in a speech to the students of ‘Aligarh, in 1938, he explained his reasons. Speaking of the Round Tables Conferences, he said: “In the face of danger, the Hindu sentiment, the Hindu mind, the Hindu attitude led me to the conclusion that there was no hope of unity. [...] The Mussalmans were like dwellers in No Man’s Land. [...] I felt so disappointed and so depressed that I decided to settle down in London”.15 The outcome of the conferences was the Government of India Act of 1935, which remained unaltered, in its principles, until the transfer of power to India and Pakistan in 1947. This is not the place to examine in detail the new law: it is enough to say that in the elections of 1937, out of thirty million voters 70 per cent were Hindu and 30 per cent were Muslims. Even so, a co-operation was impossible: Nehru said that only two parties existed in the Country, Congress and the British; Jinnah objected that there was a third party, the Muslims. The impossibility of working together derived from the fact that the Muslim League was very weak: she had got only 5 per cent of the Muslim votes. Mahatma Gandhi remained an icon but, from now on, the practical management of India’s policy passed mainly into the hands of two Hindus, Nehru16 and Bose,17 and a Muslim, Jinnah. The years 1937-39 were an interlocutory period: only the Congress participated in the new provincial legislatures, while the princely States and the Muslim League turned down federation. On the insistence of Liyaqat ‘Ali Khan,18 future Prime Minister of Pakistan, ‘Ali Jinnah returned to India to re-organize the Muslim League which in the elections of 1946 got 73 seats (out of 78 allocated to the Muslims); in the same elections the Congress got 203 seats out of 210). Hence, the two parties became the only two forces able to speak for the whole of India. Previously, on the instance of Jinnah who had converted to Iqbal’s idea of “two nations”,19 expressed by the Poet at Allahabad in 193020 and repeated in a letter of 21st June 1937,21 the Muslim League had approved at Lahore, on the 23rd March 1940, an official Resolution towards the creation of Pakistan. Four days before, on 19th March, at Ramgarh, in Bihar, the Congress had decided in favour of civil disobedience, which was however given up after the collapse of France and the German air blitz over England. Only on 8th August did the Viceroy promise to India a dominion status, but after the conclusion of the war; even the announcement that “full weight should be given to the views of the minorities” was too vague. The last hopes for India’s full independence came on 14th August 1941 from the Atlantic Charter announced by Churchill and Roosevelt: one of the eight points, in brief, stated that “all peoples had a right to self-determination”; but, soon after, Churchill made it clear that it did not apply to British India, thus creating bad feelings among the Indians for this double standard of behaviour.22 And in April 1942 after the British Army had lost Singapore, Malaya, and Burma, in a letter to a friend on 22nd April 1942, and repeated to the press, the Mahatma wrote:

My firm opinion is that the British should leave India now in an orderly manner and not to run the risk that they did in Singapore and Malaya and Burma [...] Britain cannot defend India, much less herself on Indian soil with any strength. The best thing she can do is to leave India to her fate. I feel somehow that India will not do badly then.23

The apex of the relations between Gandhi and the British was reached on 8th August 1942 when the Committee of the Indian Congress adopted the “Quit India” Resolution. In an interview to the newspaper “The Hindu”, published on 21st June, Gandhi had said that the two communities will come together almost immediately after the British power comes to a final end in India. If independence is the immediate goal of the Congress and the League then, without needing to come to any terms, all will fight together to be free from bondage. When this bondage is done with, not merely the two organizations but all parties will find it to their interest to come together and make the fullest use of the liberty in order to evolve a national government suited to the genius of India. I do not care what it is called, whatever it is, in order to be stable, it has to represent the masses in the fullest sense of the term. And, if it is to be broad-based upon the will of the people, it must be predominantly non-violent.24 Did he think of the foreseen blood-baths in an India prey of communalism, with the minorities such as the Muslims and the Sikhs, in particular, under a majority Hindu government, without the presence of a unified Indian Army and the British officers, who became suddenly without any responsible guide? At the same time, because of rumours, probably spread by the British Intelligence Service, maybe with some Muslim connivance, Gandhi was accused of leanings in favour of the Axis powers. His answer was clear:

I have no desire whatsoever to woo any power to help India in her endeavour to free herself from the foreign yoke. I have no desire to exchange the British for any other rule. Better the enemy I know than the one I do not. I have never attached the slightest importance or weight to the friendly professions of the Axis power. If they come to India they will come not as deliverers but as sharers in the spoil.25

Though the Mahatma did not doubt of Chandra Bose’s sacrifice or patriotism, he stated “that he was misguided and that his way could never lead to India’s deliverance”, hinting of course to Bose’s alliance with Japan and his leading the INA troops against British India. Besides, Gandhi’s faith in a unified India was shaken by Jinnah’s statement: “Pakistan is an article of faith with Muslim India and we depend upon nobody except ourselves for the achievement of our goal”. Prompt was the Mahatma’s answer: “If Pakistan is an article of faith with him, indivisible India is equally an article of faith with me. Hence there is a stalemate. But today there is neither Pakistan nor Hindustan. It is Englistan. So I say to all India, let us first convert it into the original Hindustan and then adjust all rival claims”.26 Although no actual preparations had been made by the Congress, the British reacted strongly: under the input of Churchill who disliked Gandhi intensely – as a matter of fact he spoke of him as the “naked faqir” – in the early hours of 9th August all the Congress leaders were arrested and the Congress was declared an illegal body. The years of the war, in particular 1942-1945, were very difficult: no Indian trusted anymore the promises of the British Government after Churchill’s declaration, which was just the opposite of the Viceroy’s statement. All the Congress leaders were in jail, shortage of food and high prices afflicted the masses, martial law was imposing, recruitment was at the pace of 50,000 men per month, war factories were built to meet the demands of the Army, the figure of the people employed increased to ten times and the production of weapons from ten to fifty times.27 The war ended in Europe in April-May 1945; new elections in Great Britain brought to power the Labour Party: on 26th July Winston Churchill was replaced by Clement Attlee whose first act was the announcement of self-government for India and the setting up of an interim government “to give the Viceroy [Lord Wavell] greater freedom in order that in the period which is to elapse while a constitution is worked out you may have a government enjoying the greatest possible support in India”.28 On 23rd March 1946 a three-men Cabinet Mission reached India: it was made up of Pethick-Lawrence, Stafford Cripps and A. V. Alexander. In spite of their goodwill, the results were nil because the contrasts between Congress and League were unsolvable - Nehru acted as the spokesman of the nation in force of his majority, Jinnah did not consider the Muslims a minority but a nation, insisting on his claim of Pakistan.29 Besides, both Congress and League wanted Great Britain to relinquish immediate authority to a sovereign interim Indian government. The entire situation can be summed up in two slogans addressed to the English: “You quit and then we will divide” (the Congress); “You divide and then quit” (the League). In a speech at the House of Commons, on 18th June, Stafford Cripps had remarked in an honest way that “the issue of ‘one or two Indias’ had been bitterly contested at the elections and the two major parties, the Congress and the Muslim League, had each of them almost swept the board in their respective constituencies” and that “the circumstances of the spring of 1946 were vastly different from those of 1942 or 1939”, adding that “India has shared to the full in the political awakening which is evident all over the world after the war and nowhere perhaps more than in the Far East”.30 This impasse was broken by the Muslim League, who supported the achievement of Pakistan by announcing a hartal against both Congress and Britain: the hartal, called “Direct Action Day”, took place on 16th August 1946 and was the beginning of massacres everywhere lasting for months. In an effort to save the situation, Clement Attlee called a meeting in London on 3rd December: it was attended by the Viceroy Lord Wavell, Jawaharlal Nehru for the Congress, M. ‘Ali Jinnah and Liyaqat ‘Ali Khan for the League, Sardar Baldev Singh for the Sikhs. After a three-day talks, the members returned to India with no solution. On 23rd March 1947, Lord Mountbatten replaced Lord Wavell as Viceroy and prepared to dispose of the British Empire of India. In spite of Gandhi’s strong opposition to the division of the country,31 on 21st April 1947 Nehru agreed officially to the idea of partition. On the evening of 3rd June, Lord Mountbatten announced the plan over All-India Radio: actually, though all Indians were happy for the recovered independence from the British crown after one and a half century of domination, none of them was satisfied for the partition. The Hindus and the Nationalists deplored the vivisection of India, the Muslims were not satisfied with the “truncated and moth-eaten Pakistan”, as M. A. Jinnah had described it. However, it was the best practicable solution of the Indian problem at the moment, even though it was not in any case the best solution. On 18th July the bill for the transfer of power to two dominions became law: Great Britain was definitely relinquishing India along with her suzerainty over the 562 Princely States, all of them, with a few exceptions, joining the new dominion of India. At midnight of 14th August 1947, the two nations of Bharat and Pakistan were born. India comprised the whole sub-continent except the territories which joined Pakistan, namely West Punjab, Sind, Baluchistan, North-Western Frontier Province and East Bengal.