|

|

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | ==Chapter 5==

| |

| | | | |

| − | THE ROLE OF THE IPO AND THE ISMEO

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Within the framework of propaganda and support of the fascist regime two cultural institutions were created in the Twenties and Thirties: the IPO and the IsMEO.

| |

| − | Actually these two institutions were primarily devoted to the study and spreading of the culture of the near, middle and far eastern countries: but they were created in a short time and financed by the government because of their possibility of being a fifth column of the fascist propaganda in the oriental world.

| |

| − | The Institute for the East, IPO [Istituto per l’ Oriente], was created in 1921 in order to publish information, articles and notes on the near-east countries. The Italian Institute for the Middle and Far East, IsMEO [Istituto per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente] was founded in 1933 with a double aim to promote the studies and researches concerning Asian countries and to favour the presence of Italy in those countries from a political and economic point of view.

| |

| − | After the conquest of Libya in 1912, the Italian interests in a territorial colonial expansion increased along with the commercial penetration in the Arab countries of the Mediterranean. The hopes of Italy in an international mandate after the First World War were frustrated by the partition policy of France and England; in Italy the supporters of a more visible presence in the Levant gained ground. In Eritrea the governor Jacopo Gasparini went saying that Eritrea was the starting point of a further expansion both for economical and commercial reasons as well as for the Italian prestige.

| |

| − | The advent of Fascism made things easier: the Arab countries, which had dreamt of an Arab nation after the war and had been frustrated in their expectations, found in Italy a favourable ground for their aspirations to liberty and independence. Fascism and Mussolini exploited these hopes in their anti-British policy.

| |

| − | The real founders of the IPO were a scholar, Carlo Alfonso Nallino,1 and a high officer of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Amedeo Giannini,2 with the personal support of duke Giovanni Antonio Colonna di Cesarò, who had been since 1910 the soul of the Italian Colonial Institute and was the first president of the IPO. Carlo Alfonso Nallino, an Arabist, was until 1938 the scientific soul and coordinated the work of his not less famous colleagues such as Michelangelo Guidi, Ettore Rossi, his successor, Virginia Vacca, Laura Veccia Vaglieri, and Enrico Cerulli, to quote the prominent of them. Amedeo Giannini was the political soul, a sort of adviser and an unofficial representative of his Ministry. Both of them showed their skilfulness in the management of the monthly magazine “Oriente Moderno”, which performed the task of keeping Italian readers informed of the events in the Muslim world; besides this, the magazine contained a politico-cultural section with articles of high standard, even though most of them were written under the input of its promoters.

| |

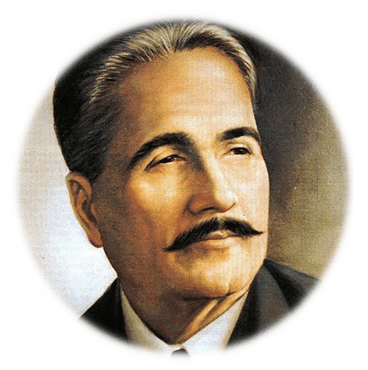

| − | Let us deal here with the Indian Muslim world, in particular with reference to the work of Muhammad Iqbal.

| |

| − | The first record of Iqbal’s activity appeared in the second volume of “Oriente Moderno” (1922-23, p.191): it was a note by Carlo Alfonso Nallino who wrote that Iqbal’s “philosophical Persian poem Asrar-i Khudi [The Secrets of the Self] is actually a cry of Muslim revolt against Europe, a demonstration of the strongest aspirations of Pan-Islamic irredentism”.

| |

| − | In 1932 Muhammad Iqbal published at Lahore his most famous poem Javed-nama. In the same year, in December issue of the magazine,3 Maria Nallino published an article giving the summary of Iqbal’s poem. Actually it was not an original contribution since no scholar would have been able to read and understand the poem in a short time. It was the translation of an unsigned article in English, published in “The Muslim Revival” at Lahore in June same year; however the notes were original and the title in which the Javed-nama was compared to the Divine Comedy. Since then Iqbal magnum opus has been called the “Divine Comedy of the East”.

| |

| − | This particular interest of the board of the magazine “Oriente Moderno” for Iqbal’s work in the Thirties of last century derived from two relevant elements: the first was that Italy had always considered in a sympathetic way the problems of the Muslims in India, the second was Iqbal’s meeting with Mussolini.

| |

| − | In 1934, the year in which Iqbal published in London his lectures on The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, “Oriente Moderno” published, in an Italian translation, an English article by Arthur Jeffery, a professor of the American University of Cairo. Though the article4 reflected the personal point of view of the author, it was informative on the role of the Qur’an in modern times.

| |

| − | With the outbreak of the Second World War “Oriente Moderno” increased its propagandistic character, though it maintained its cultural purpose. An Indian Muslim student, who got a degree in Italian literature in Rome, Reyaz ul-Hasan, was given the task of writing in 1940 a long article on the life and work of Iqbal. It was a very interesting and explicative article,5 because it was the first to be written in original Italian with direct translations from Iqbal’s Urdu and Persian poems.

| |

| − | The necessity of an exhaustive handbook on the 19th century history of Muslim India brought in 1941 to the publication of L’India Musulmana [Muslim India]: written by Virginia Vacca, a member of the editorial staff of the magazine, it was published by the Institute for the Studies of International Politics in Milan.

| |

| − | The role played by the IPO could have been more efficacious if there were not rivalries among the many bodies interested in the colonial policy of Italy: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry for Colonies, the Oriental Institute of Naples re-organized in 1926, and the IsMEO created in 1933, not to speak of the tensions between these institutions and the governors of the various colonies. Many were the misunderstandings and the boycotting actions by the members of these bodies, which were more or less formed with the same people belonging to more than one of them.

| |

| − | The situation became worse when it was decided, with the consent of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the approval of Mussolini, to publish in 1932 a bi-monthly magazine “L’Avvenire Arabo/al-Mustaqbal al-‘Arabi” in Italian and in Arabic; the editor-in-chief was a Syrian journalist, Munir Lababidy, who expressed the programme of the paper in Arabic thus:

| |

| − | Our main aim is as follows: we want to inform the Italian readers of oriental life, of Arab life in particular, in the Italian language [...] and the Arab readers of the news about them in the West in the Arabic language [...], in particular of this noble nation where we live, of the qualities and virtues which helped her to rise again thanks to her new regime and to the devotion her citizens have for their great Duce.6

| |

| − | Notwithstanding this captatio benevolentiae, the third issue of the magazine which appeared on 15th February was confiscated because an article concerning the dispute between Hejaz and Yemen had been considered an extolling of the Arab people: one thing was to inform, another thing was to glorify a population under a colonial government – thought the Italian Ministry for Colonies. The situation became worse: the Ministry for Colonies prohibited the diffusion of the magazine in the colonies, which meant practically its inefficacy. On 16th June the Minister for Colonies Emilio De Bono7 expressed his negative opinion: the rivalry between his Ministry and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had broken openly. Too divergent was the policy of the two ministries: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs wanted to show the good willing of fascist Italy and her support to the Arab aspirations, while the Ministry for Colonies could not consider the Arabs on a parity level in a period of opposition to the fascist rule by many nationalistic Arab groups. On 31st October 1932 the magazine stopped publication after the brief life of twenty issues.

| |

| − | Eight years after, with the break of the Second World War, the IPO started publishing in December 1940 a new fortnightly magazine, “Mondo Arabo”, this too in Italian and Arabic, but with a clear propagandistic purpose, anti-British, anti-Zionist, pro-Arab. It is enough to quote an article, “The Mediterranean to the Mediterranean peoples”, to understand the policy of the magazine:

| |

| − | In the new Mediterranean order the Arab peoples will be given the task according to the civilization, the history and the aspirations of the Arab Nation [...]. There will be no place for a Zionist State in the new Mediterranean! [...]. To attain this destiny Italy is now fighting, on the sea which belonged to Rome, to attain this destiny the Arab Nation will not take a long time to side with the Axis countries who represent justice.8

| |

| − | The IsMEO was founded in 1933 under the input of Giuseppe Tucci,9 then a young scholar of Indology and Tibetology, under the chairmanship of the philosopher Giovanni Gentile;10 however, because of Gentile’s political commitment, all the work was carried on by Giuseppe Tucci. Officially the IsMEO [Italian Institute for the Middle and Far East] was created to the purpose of developing the cultural relations with Asia countries; practically its aim was to emphasize the presence of Italy in those countries with a particular eye to the political and economic problems.

| |

| − | At the beginning of 1931 the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs contacted the Italian National Institute for Exporting and some banks to explore the possibilities of creating an Institute in-charged with the task of collecting economic information on India and distributing some scholarships to students from India. In the same period Giuseppe Tucci sent to Gino Scarpa, Consul General in Calcutta, a similar, but cultural project concerning an exchange of students with India, scholarships for Indian students, and archaeological research in India. In between there was a third project, an economic one with some cultural aspects: in November 1929 Corrado Gini, President of the Central Institute for Statistics, had met in Geneva a professor of Calcutta University, Benoy Kumar Sarkar, then visiting professor at Munich University, who was interested in a project of an institute for economic relations between India and Italy. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Mussolini were directly or indirectly aware of all these projects.

| |

| − | However, the right person was Giuseppe Tucci. He had been for five years in India, teaching at the Universities of Calcutta and of Shantiniketan, where he was in very friendly relations with Tagore, and had met Gandhi. Besides he was held in great favour by the British and his four scientific expeditions to Ladakh had been praised by the Indian press. Scarpa, Mussolini’s longa manus, had written in a report to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that, “for his position with the British and the Indians, Tucci is a precious element in the future”. One of his students, P. N. Roy, who became professor of Italian at Calcutta University, had translated into Bengali a biography of Mussolini and compiled anthology of his speeches, Mussolini and the Cult of Italian Youth.11

| |

| − | Back from India, on 16th March 1931 Tucci sent to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Dino Grandi, a report of his mission to India and a full draft of his proposal concerning the creation of an Institute: this draft combined the first two projects, excluding the third one limited to India and Italy. The Ministry, on the contrary, prepared its own draft where the aims of the institute were “cultural apparently”, but “economic in reality” and political deep down: Dino Grandi approved of it on the following 17th April.

| |

| − | Two events contributed to the definitive creation of the IsMEO.

| |

| − | Kalidas Nag, the director of the India Bureau, a cultural association for the development of co-operation between India and the western countries, excluding Britain, visited Rome, delivered speeches at Rome University and at the “Accademia d’Italia”, and concluded an informal agreement with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs about a future exchange of students. Nag was in good terms with Tucci, whom he had met during his stay in Calcutta.

| |

| − | On Tucci’s suggestion, Giovanni Gentile supported the creation of the institute, prepared a new draft along the lines of the Fascist Institute of Culture, where both cultural and economic interests were indicated, submitted it directly to Mussolini and got it approved in July 1932.

| |

| − | After the settlement of juridical and financial problems, the IsMEO came into being on 21st December 1933 with an opening address by Giovanni Gentile and a lecture by the geographer Filippo De Filippi on “The Italian Travellers in Asia”. In the very beginning of his address Gentile stated:

| |

| − | The Italian Institute for the Middle and Far East which we are opening today has been founded to promote and develop the cultural relations between Italy and the countries of central, southern and eastern Asia; besides (as indicated in article 1 of its Statutes), to examine the economical problems concerning these countries and Italy.12

| |

| − | However, the real fact that the Institute was mainly interested in India was underlined in the next paragraph when the philosopher said that “the first stimulus to maintain spiritual relations came from the most influential and representative persons of the great India”.

| |

| − | At the same time a Congress of Asian Students was held in Rome: it was attended by about five hundred students and by the ambassadors of the middle and far-east countries. The political importance of this event was underlined by Mussolini’s speech on 22nd December 1933, which was read in Italian, English, French and German. The Duce took advantage of this opportunity by criticizing the lack of relations between the Latin and Oriental worlds due to a non-Mediterranean civilization, a false civilization based on the pillars of subjugation and exploitation [Britain]:

| |

| − | In the evils Asia laments, in her grudges, in her reactions we see our own face reflected in them. [...] Today Rome and the Mediterranean with their fascist rebirth, above all a spiritual rebirth, are going on with their unifying function. It is because of this that the new Italy has gathered all of you here. As in other occasions, in periods of moral crisis, the civilization of the world was saved by the co-operation between Rome and the East, today [...] we Italians and Fascists hope in our common millenary tradition of constructive co-operation.13

| |

| − | This idea was stated clearly three months after, on 18th March, when speaking in Rome at the second five-year Assembly of the Regime: “The historical goals of Italy have two names - Asia and Africa. South and East are the cardinal points that must become the Italians’ interest and will”, meaning that Italy had to take Britain’s place in Asia after the collapse of the British Empire. But, immediately after he added: “I am not speaking of territorial conquests, but of a natural expansion which must take to a co-operation between Italy and the peoples of Africa, between Italy and the nations of the near East”.14 It was a re-assuring message to England: Italy’s expansion was supposed to be only commercial, but Mussolini was planning the conquest of Ethiopia in secret.

| |

| − | Among the Indian students who worked for the IsMEO the most active was Monindra Mohan Moulik, former secretary of the Indian Press Association of Calcutta, who got a Ph. D. in political sciences at Rome University; he contributed with many articles to the magazine “Asiatica” and was a correspondent from Rome for various Indian newspapers, in particular the “Amrita Bazar Patrika”, near to Bose’s positions. For the IsMEO he delivered on 4th April 1936 an interesting lecture on Il fondamento ideale del nazionalismo indiano [The Ideal Fundamentals of the Indian Nationalism] which is significant of the climate of that period. In spite of the fact that Moulik stated that the Gandhism was the vital force of the Indian Nationalism, he concluded that the external form of the political organization of the movement might take the form of fascism and national-socialism. Actually, a contradiction because this was the program of S. C. Bose, that is a sort of synthesis [samyavada] of fascism and communism, quite the opposite of Gandhi’s non-violence .15

| |

| − | In 1935 the IsMEO began publishing a Bulletin of information, which a year after became a magazine “Asiatica”. In the same period, in 1934, an Institute for the Studies of International Politics (ISPI) had been created in Milan; operating under the supervision of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, its aim was mainly political. It promoted the study of international politics and economics, particularly international affairs and strategic problems, through a magazine “Relazioni Internazionali”, a semiofficial paper, which covered the contemporary aspects of the Italian international policy.

| |

| − | “Asiatica” and “Relazioni Intenazionali” devoted much space to articles, information and notes on the Indian events, in particular on Gandhi, Nehru, and Bose, though many were purposely distorted or rigged.

| |

| − | Gandhi was described as a champion of humanity, a religious man and an apostle rather than a politician, a visionary and a dreamer, in other words a great figure, but with no practical sense: “The British will never get pushed out of India by means of prayers, fasts, and goat milk diets” – wrote E. Canevari, who, however, pointed out that his philosophy might well be admirable.16 Other writers went farther off by describing him as an agent of the Jewish-Marxist International17 or as an instrument of a world Masonic conspiracy!18

| |

| − | Tens of references were dedicated to C. Bose who was considered in those years the fascist forte: at least up to 1943 “Relazioni Internazionali” regularly published Bose’s appeals to his people to keep united and to fight the British on the side of India’s natural allies.19

| |

| − | NOTES AND REFERENCES

| |