BEDIL IN THE LIGHT OF BERGSON

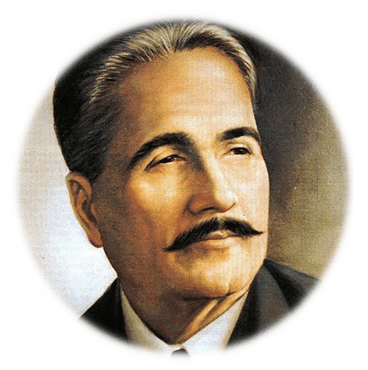

From IQBAL

INTRODUCTION

Iqbal was a poet of immense erudition. He benefited from the literary and philosophical sources of the Orient and the Occident alike. His literary production mainly consists of poetry but he occasionally expressed himself in prose too. Apart from his two books , most of his speeches, statements and writings have also been edited in many volumes , but the possibility still remains that one may come across an unpublished statement or an article of the poet. It is my privilege to present here one such article entitled “Bedil in the Light of Bergson”. Written in the poet’s own hand–writing, the original article is preserved among the Iqbal material in the 1qbal Museum. I am indebted to Mr. Muhammad Suheyl Umar for drawing my attention to, and then helping me in obtaining the photocopy of, the article.

It would not be out of place if, before discussing the article itself, we briefly mention what Iqbal thought and wrote about the philosophy of Bergson and Bedil.

From his early days to the end of his life, 1qbal spoke very highly of the poetry of Bedil (1644 1720) and his dynamic philosophy. He has mentioned Bedil more than once in his writings–both in his letters and statements, poetry and prose reflections. In one of his letters to S.M. lkram, praising his work on Ghalib, he frankly expressed his candid opinion about the influence of Bedil on Ghalib and said that inspite of all his efforts, Ghalib could not succeed in imbibing the spirit of Bedil, though he succeeded in imitating his style. In a letter to Mian Bashir Ahmed, 1qbal has emphasised the point that a comparative study of Ghalib and Bedil apropos of their poetry is necessary. In addition to this, it is also imperative to see how far the philosophy of life enunciated by Bedil impressed Ghalib and how far he (Ghalib) could grasp this philosophy. Iqbal was also of the opinion that both in and outside India the contemporaries of Bedil could not comprehend the theories of life enunciated by the poet. On another occasion, answering to a question of Mr. Majeed Malik, he expressed the opinion that Bedil’s style could not gain currency in Urdu.

In his Stray Reflections – a conspectus of his early odd jottings based on the impressions belonging to his period of flowering – he pays glowing tributes to Bedil, as he does to so many other poets and philosophers, indigenous and otherwise. In one such “reflection” he says categorically:

“I confess I owe a great deal to Hegel,Goethe, Mirza Ghalib, Mirza Abdul Qadir Bedil and Wordsworth. The first two led me into the “inside” of things, the third and fourth taught me how to remain oriental in spirit and expression after having assimilated foreign ideals of poetry and the last saved me from atheism in my student days”

Again under the title “Wonder”, 1qbal compares what Plato and Bedil have said about it. He is of the opinion that the standpoint of Bedil and Plato about “Wonder” is opposed to each other. Thus runs the impression of 1qbal:

“Wonder, says Plato, is the mother of all science. Bedil (Mirza Abdul Qadir) looks at the emotion of wonder from a different standpoint. Says he:

نزاکت ہاست در آغوش مینا خانۂ حیرت

مژہ برہم مزن تانشکنی رنگ تماشا را

To Plato wonder is valuable because it leads to our questioning of nature, to Bedil, it has a value of its own, irrespective of its intellectual consequences. It is impossible to express the idea more beautifully than Bedil.” 1qbal is so enamoured of Bedil that he at times quotes his verses and reveals certain features of his poetry and at times exhorts his friend Kishan Parshad Shad to edit the divan of Bedil. What impressed Iqbal most was not only the style of his poetry but also his life style. Comparing the mystic attitudes of Bedil and Ghalib, Iqbal had once remarked that “the mysticism of the former is dynamic and that of the latter is inclined to be static”. Not only in prose but also in his poetry, Iqbal has mentioned Bedil twice. In Bang e Dara, he proclaimed Bedil as مرشدِ کامل (the Perfect Mentor) in a poem entitled مذہب and inserted his famous couplet at the end of the poem: با ہر کمال اندکے آشفتگی خوش است ہر چند عقلِ کل شدہ ای بے جنوں مباش

In Zarb e Kalim, under the title “Mirza Bedil” , the poet touches on the problem of the nature of the Universe and concludes by quoting a couplet from Bedil, which according to him beautifully throws open the gate of this “wonderland”. The couplet is: دل اگر می داشت وسعت بے نشاں بود ایں چمن رنگِ مے بیروں نشست از بسکہ مینا تنگ بود

Now the question arises: why is Iqbal so much enamoured of Bedil? It is because both the poets hold a similar view of Reality. Though Iqbal, on some occasions, as is evident from the article under review, shows his differences with regard to the pantheistic attitude of Bedil, he praises him for his deep insight into the human mind. Again both the poets consider intuition to be a powerful and effective means of apprehending Reality. Both are of the opinion that the dry as dust rationalism does not work. They also share the unshakable belief in the potentialities of man and hold the view that man can move mountains and conquer not only the forces of nature but can also attain to the highest sublimities, ever dreamt of. Through a host of similes, metaphors and symbols, Bedil makes this point clear. At places he unfurls the banner of human greatness and declares that the mount Sinai has borrowed its resplendence from his glow-worm (a warm and spiritualized human heart) while on other occasions he exhorts man to find out his potentialities which can only be discovered if he tears up the veil which hides the treasure from his eyes: حیف نشگافتیم پردۂ دل دانہ بودہست مہر خرمن ہا

کدام رمز و چہ اسرار خویش را دریاب

کہ ہر چہ ہست نہاں غیر آشکار تو نیست

ہر دو عالم خاک شد تابست نقش آدمی

اے بہار نیستی از قدر خود ہشیار باش

موج دریا در کنارم از تگ و پویم مپرس

آنچہ من گم کردہ ام نایافتن گم کردہ ام

اے طلب در وصل ہم مشکن غبار جستجو

آتشم، گر زندہ می خواہی ز پا ننشاں مرا

بحسن خویش نگاہے کہ در جہان ظہور

خطاب احسن تقویم داری از خلاّق

The instances can, no doubt, be multiplied but I think these are sufficient to make clear the similarities of both the poets. The above verses remind one of what Iqbal has said on the subject in a similar vein. A few such verses are given below: حسن کا گنج گرانمایہ تجھے مل جاتا تو نے فرہاد نہ کھودا کبھی ویرانۂ دل

شاھدِ اول شعورِ خویشتن خویش را دیدن بنور خویشتن

آشنا اپنی حقیقت سے ہو اے دہقاں ذرا دانہ تو، کھیتی بھی تو، باراں بھی تو، حاصل بھی تو

عالم سوز و ساز میں وصل سے بڑھ کے ہے فراق وصل میں مرگ آرزو، ہجر میں لذت طلب

از شریعت احسن التقویم شو وارثِ ایمانِ ابراہیم شو

It is, perhaps, because of such similarities that both the poets share, to some extent, a common diction. It would be a very interesting study to discern a common diction of both the great poets but it is not the right place to attempt it. Suffice it to say that Iqbal was greatly inspired by his predecessor and it is owing to this inspiration that a diction similar to that of Bedil has naturally percolated through his poetry. The combination of words such as فیض شعور، قافلۂ رنگ و بو، آئینہ دار ہستی etc. etc., makes it clear. Dr. Abdul Ghani in his book Life & Works of Abdul Qadir Bedil has given a long list of such combinations of words which in one way or another, have the imprint of Bedilian style. It is also interesting to note that both Iqbal and Bedil were much averse to those forms of mysticism which had deviated from its centre, freed itself from the Divine Law and assumed the form of quite an independent “Tariqa”.. In “Bedil in the light of Bergson”, 1qbal expresses his deep aversion to such mysticism and reacts strongly against it. He calls it ‘Persian Mysticism’ which has hardly anything in common with the Islamic sufism. In many of his writings Iqbal expresses his deep indignation against this plain aberration as is amply evident from his preface to the first edition of the Secrets of the Self and in his incomplete book on Tasawwuf, in addition to what he has said against it in his letters and in his poetry. As for Bedil, he expressed his reaction against this kind of mysticism which he declared as something “meaningless”: در مزاج خلق بیکاری ہوس می پرورد غافلاں نام فضولی را تصوف کردہ اند

But it does not mean that the tasawwuf brought forward by Bedil is wholly acceptable to 1qbal. Iqbal also objects to it at length and declares that in its ultimate analysis it is nothing short of the idea of “Descent” – much loved and propagated by the pantheistic sufis– and quite contrary to the spirit of Islam. It may, however, be left to the reader to decide for himself whether the tasawwuf of Bedil is pantheistic in essence or panentheistic as is insisted by some scholars of Bedil. As to the birth place of Bedil, 1qbal has mentioned him as “Mirza Abdul Qadir Bedil of Akbarabad” in his article under discussion. In his famous “Lectures” he again expresses the same view. Now as far as the birth place of Bedil is concerned, various Tazkira writers have mentioned various places. Mir Qudrat ullah Qasim says that Bedil was born in Bokhara and Nassakh follows him in this regard. Khushgo is of the opinion that Bedil was born in Akbarabad while Delhi and Lahore have also been mentioned in this connection by Raza Quli Hidayat and Tahir Nasrabadi respectively. May be because of such contradictory opinions, 1qbal picked Akbarabad to be the birth place of Bedil. However it has now been established both from the internal evidences of Bedil’s poetry and from the writings of his contemporaries (the most reliable of his contemporaries being Mir Ghulam Ali Azad Bilgrami) that Bedil was born in what was known in the Buddhist era as Patliputra and what is now known as Patna (Azimabad) Perhaps enough of Bedil. We now turn to Bergson (1859¬-1941) who remained a favourite of Iqbal throughout his life and from whose writings Iqbal has gleaned considerably. It may be noted here that the theories of “Elan Vital” and “Intuition” amply propounded by Bergson in the last quarter of the nineteenth century gained a wide popularity in the first half of the twentieth century. The concepts of Reality put forward by Iqbal and Bergson have many common elements. Iqbal was much fascinated by the concept of Pure Duration propounded by Bergson and both in his poetry and prose he elaborated it forcefully. In the Secrets of the Self under the title الوقت سیف (Time is a Sword) Iqbal quotes Mohammad bin ldrees Ashshāfiee who called Time as “the cutting sword” and then proceeds to elaborate the theory of pure duration adding the ahadith لی مع اللہ وقت and لا تسبوا الدّھر in support of the Real Time. He accosts those who are “Captives of tomorrows and yesterdays” and urges them to see a Universe that lies hidden in their hearts. Time, which these short sighted people have taken for a straight line with nights and days as dots on it is, in reality ever lasting and indivisible: باز با پیمانۂ لیل و نہار فکر تو پیمود طول روزگار

تو کہ از اصل زماں آگہ نہ ای از حیات جاوداں آگہ نہ ای

اصل وقت از گردش خورشید نیست وقت جاوید است و خور جاوید نیست

وقت را مثل مکاں گستردہ ای امتیاز دوش و فردا کردہ ای

اسرار خودی/کلیات اقبال )فارسی(، ص 72 In the poem quoted above, 1qbal has not mentioned Bergson but it is clear from its contents that the concept of Time has been enunciated in the light of Pure Duration which is the corner stone in the philosophy of the French philosopher. In his preface to Pyām e Mashriq (1923), 1qbal has given us the tidings of a new world with a new man that is emerging out of the ashes of the old world. According to the poet a silhouette of this new man and the dim contours of this new world can be seen in the writings of Einstein and Bergson. In the same book, 1qbal delivers a message from Bergson as" پیغام برگساں" in which the intuitioned philosopher advises humankind to bring forward an intellect which has drawn inspiration from the heart because only such intellect can comprehend the mystery of life. Now this is another name for intuition the kernel of the Bergsonian philosophy. Intuition, according to Bergson, is a direct apprehension of Reality which is non intellectual. In intuition all reality is present. It does not admit of analysis because in analysis all is over and past or not yet. But what does this intuition bring to us? This has been answered pertinently by H. Wildon Carr. He says: “What intuition does for us is to give us another means of apprehension by a fluid and not a static category; in apprehending our life as true duration we grasp it in the living experience itself and instead of fixing the movement in a rigid frame follow it in its sinuosities; we have a form of knowledge which adopts the movement” Now the question arises why did Bergson lay such a stress on intuition and how can he say that the Ultimate Reality of the universe is spiritual? The answer is that after deep observation and still deeper insight into the phenomena of life, Bergson had reached the conclusion that the intolerant and haughty cult of science which was so prevalent and pervasive in his days and had pretensions of being all knowing touched only the surface of the human self and could not fathom the depths of the ocean of the Universe. How very strange that all metaphysics had been thrown aside as “Fantasy” in his days while Bergson thought and, Indeed, very rightly that science was ill-¬suited to grasp the Reality in its entirety and it could only be grasped with the help of intuition. He was of the view that a genuine metaphysics results from intuition and not from intellectual activity. He was of the opinion that it was the soul that brings the past to act in the present and is the only unifying factor between the past and the future. Hence the life a perpetual and unceasing flux. Bergson has elaborated this “unceasing flux” in the following words: “I find first of all, that I pass from state to state. I am warm or cold, I am merry or sad, I work or I do nothing, I look at what is around me or I think of something else. Sensations, feelings, volitions, ideas– such are the changes into which my existence is divided and which colour it in turns. I change, then without ceasing.” This unceasing flux, this formidable impetus equally governs every living being and the whole of humanity, according to Bergson, is one immense army galloping beside and before and behind with a view to beat down every resistance and clear the most formidable hindrances. Apparently, it seems that the forces that hinder and thwart this unceasing flow of life are something foreign to it. For example matter may apparently be regarded as inimical to the spiritual reality and may thus be declared as something detached from it. Bergson’s Elan vital, however, does not admit of any such detachment or separation. In the article under discussion 1qbal has expressed the same view and almost exactly in the same way as the famous exponent of Bergson – Wildon Carr has. Wildon Carr says: “The spiritual reality, then, which philosophy affirms is not reality that is detached from and foreign to matter, superposed upon matter, or existing separately from matter. It is not the assertion that there is a psychical reality, but that the one is the inverse order of that which is the other. Physics is, to quote a phrase of Bergson, inverted “Psychics”. The two orders of reality are not aspects, they are distinguishable and yet inseparable in an original movement, the absence of one order of being is necessarily the presence of other.” And now something more about the article that is being introduced in the following pages. In “Bedil in the Light of Bergson” what is astonishing, is the striking similarities that Iqbal has discerned between the two master minds. Instead, it would perhaps be more accurate to say that these similarities are not circumscribed to Bedil and Bergson alone but can be found in 1qbal’s philosophy also. But it must also be noted that Iqbal has also his points of divergence. His familiarity with Bedil and Bergson is not one of unquestioning fidelity to them. He has, at points, very pertinently criticised the philosophy of both Bedil and Bergson and has posed very pungent questions with regard to the Sufi idea of “Descent” in case of Bedil and to the idea propounded by Bergson that intelligence is a kind of original sin and with a view to reaching the core of Reality one must revert to the pre-intelligence condition as Bergson insists. In a similar vein, 1qbal has raised serious questions as to the total validity of Intuition. In, his lecture “The Revelations of Religious Experience”, Iqbal has paid homage to Bergson as well as criticised him on certain points. For example, Iqbal is of the opinion that unity of consciousness has a forward looking aspect also which Bergson has totally ignored. 1qbal thinks that the error of Bergson consists in regarding pure time as prior to self to which alone Pure Duration is predicable. Some such objections taken together with those raised in the article under review, form almost a pithy critique of Bergson; much beneficial and, intriguing for the students of philosophy. In the article under review 1qbal’s attitude towards the sublimation of man is as pronounced as in his other writings especially in his poetry. He believes in self¬-fortification: بخود خزیدہ و محکم چو کوہساراں زی چو خس مزی کہ ہوا تیز و شعلہ بیباک است

He has lashed out severely on the idea of annihilation which according to him is the vice of all Persian Sufism. Discussing the sufi idea of “Descent” in the article under discussion, Iqbal is of the view that this idea is Manichaean in spirit. Manichaeanism, according to our poet, not only influenced Christianity but Islam also. He is of the opinion that: “The Arabian conquest of Persia resulted after all in the conversion of Islam to Manichaeanism and the old Persian doctrine of the self-darkening of God reappeared in the form of the sufi idea of ‘Descent’, combined with an asceticism thoroughly Manichaean in spirit.” It is quite evident from the above extract that Iqbal thought the idea of “Descent” and “Asceticism” thoroughly Manichaean in spirit and held the conquest of Persia responsible for the “conversion” of Islam to Manichaeanism. It is strange that Islam, much stronger in spirit and culture, could have submitted to Manichaeanism so much so as to undergo a Manichaean conversion. It is a very debatable question. But this question aside, the interesting thing is that what Iqbal wrote in 1910 in his Stray Reflections about the Muslim conquest of Persia is diametrically opposed to the notion he expresses in the present article. He had written under the title “The Conquest of Persia”: “If you ask me what is the most important event in the history of Islam, I shall say without hesitation: ‘The Conquest of Persia’. The battle of Nehawand gave the Arabs not only a beautiful country, but also an ancient civilization, or more properly, a people who could make a civilization with Semitic and Aryan material. Our Muslim civilization is a product of the cross fertilization of the Semitic and the Aryan ideas But for the conquest of Persia, the civilization of Islam would have been one sided. The conquest of Persia gave us what the conquest of Greece gave to Romans “ The comparison of both the extracts given above not only makes manifest the contradictions but also shows that the present article might have been written much after 1910 and probably in 1916 or thereabout. Although, to the question as to when the article under review was written, nothing can be said precisely, internal evidences, however, reveal that the article might have been written in 1916 or thereabout. My contention is that, in this article, 1qbal’s opposing and rather indignant attitude towards Persian Sufism is reminiscent of his writings on the same subject during 1915 1917. Besides the preface and certain articles alluded to earlier, his letters to certain literary luminaries during the period also show his aversion to the Persian sufism. For example in 1917 he wrote to Syed Sulaiman Nadvi: “Tasawwuf-e-Wujudi” is nothing short of an alien plant on the soil of Islam and nourished in the mental climate of the “Ajamites. How far is this notion different from the one which he expressed in his Development of Metaphysics in Persia (1908) in which he had very vehemently repudiated this idea, propounded by E. G. Browne! It must also be noted that 1qbal’s stay in Europe was a turning point in his life and after 1910, he constantly pondered over the question of Muslim revivalism and the concept of Self. Iqbal has expressed elsewhere that he gave a serious consideration to the concept of ‘Self’ for at least fifteen years. He had at last reached the conclusion that one of the most potent factors of the decay of Muslim culture was the Persian mystic thought and practices that had entered the Islamic organism and had sapped its energies. This idea formed its final crystallization in 1915 when his book The Secrets of the Self was published for the first time and caused a lot of stir, commotion, indignation, disparagement and agitation among the traditional pantheistic sufi circles. The present article, especially the portion consisting of his criticism of Pantheistic Sufism, it seems, is the ramification of what he had written in The Secrets of the Self on the subject. Lastly, It seems that once written in a running hand with much editing and pruning, the article was put aside and was never reviewed by the author. That is why there are certain omissions. A few spelling mistakes also crept into the text. We have given the missing words in the brackets and the spelling mistakes (not more than three or four) have also been corrected. At places it was deemed necessary to add some notes. These will be found at the end of the article. In the end I would like to thank Mr. Mohammad Salim ur-¬Rehman for his help in deciphering certain words that were not easily readable. [[BEDIL-IN-THE-LIGHT-OF-BERGSON]]